NotPetya – a Threat to Supply Chains

Ukraine is a nation under digital siege. Over the past few months, it has suffered through four widespread infrastructure attacks, with the Russian government being suspected as the driving force behind the attacks — although to date, there’s no clear evidence of this.

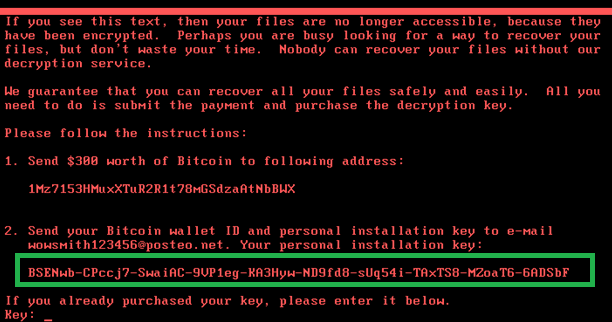

The most recent attack, “NotPetya,” occurred on June 27 th, and was initially reported as a massive ransomware attack that utilized the “EternalBlue” exploit/ vulnerability, and that large numbers of computers were being infected via poisoned email attachments.

Early reports helped to create a kind of “fog of war” over the digital battlefield that made it difficult for cybersecurity experts to respond effectively.

Now that the dust has settled, we know that there was a lot more to the attack than was initially reported. Below is a detailed summary:

Months in the Making

It is suspected that a hacking group calling themselves “The Telebots” was responsible for the “NotPetya” attack on Ukraine. They are thought to have orchestrated it, not by going after individual companies directly, but by infecting their supply chain.

This, by itself, is a deviously ingenious strategy, because when companies use off-the-shelf software provided by third party vendors, they inherently trust that subsequent software updates will not contain malicious code. In this case, however, that’s exactly how the malicious code was introduced.

The first thing the hackers did was to compromise the servers of a software vendor that serviced a large number of Ukrainian companies. In this case, the target was Intellect Service, a company that sells accounting software called MEDoc.

That is significant because, in Ukraine, companies are mandated by law to use government-approved tax and accounting software, and MEDoc has captured a staggering 80% of the market.

Unfortunately, according to the results from the forensic investigation that followed in the wake of the attack (conducted by Cisco, ESET, and other companies that offered to assist), Intellect Service unsuspectingly made it very easy for the hackers to infiltrate their systems.

The attack began when an unknown actor (believed to be a member of the Telebots), was able to gain root-level access to the server via credential theft. Then, one of the first details that came to light in the investigation was the fact that Intellect Services had stopped patching their own internal servers back in 2013.

Beginning in mid-April of 2017, more than two months before the attack was launched, the hackers used these compromised credentials to do a variety of prep-work, including installing a PHP Webshell on the company server, and adding backdoors to the MEDoc code that they could later exploit.

According to Anton Cherepanov, a malware researcher at ESET, “It is unlikely that attackers could do this [adding backdoors] without access to MEDoc’s source code.”

Like most other software vendors, Intellect Service’s popular accounting software has an auto-update feature that’s designed to push security fixes to its clients. In this case, the update function wound up pushing “poisoned” updates that allowed the hackers remote access to their systems. Further, it is believed that the injection included the ability to extract downstream credentials, giving the malicious actors additional network access to unsuspecting victims and their employees.

The Hackers Didn’t Stop with Just One Attack

The group behind the attack clearly knew what they were doing. Rather than infecting one update with a backdoor, over a two-month period the attackers managed to create three different updates that contained backdoors, allowing them to run arbitrary commands and queries through the update infrastructure.

Even worse, “NotPetya” wasn’t the only malware the Telebots were planning to deploy. There were actually two, with the others being a malware strain known as XData, which looked like AES-NI. PSCrypt was based on Globe Imposter Ransomware. The worst malware was “NotPetya,” which was based on Petya, as well as a WannaCry lookalike.

Cherepanov stated that two of the attacks were “launched just days after a backdoored MEDoc update was released.” In terms of specific timing, the NotPetya outbreak occurred five days after a June 22 update, and the XData outbreak occurred after the May 15 update.

Of particular interest, and one of the reasons that the XData attack didn’t receive as much press as the NotPetya attack, was the company’s unplanned software update on May 17, which helped to take some of the sting out of the XData attack. During the intervening days, many users had already installed the update, thus removing the backdoor.

According to Cherepanov, “They pushed the ransomware on May 18 th,” – to versions of MEDoc that still had the backdoor – “but the majority of MEDoc users no longer had the backdoored module as they had updated already.” He also said that he “suspects the May 17 update caught attackers by surprise.”

That certainly seems to be the case, and if so, then Intellect Service caught a break on that front, and inadvertently reduced the amount of damage that the XData attack could have caused.

The Big Prize – EDRPOU Numbers

Ukrainian police raided Intellect Service’s corporate offices and seized the MEDoc servers. Hackers still made off with a big prize, despite the abrupt ending.

That “big prize” takes the form of EDRPOU Numbers.

In Ukraine, every business is required to have a unique legal entity identifier known as the EDRPOU code, which is reflected in every MEDoc software installation.

Researchers from the security firm ESET stated that besides adding a backdoor, “attackers also injected code that cataloged EDRPOU numbers in installed versions of the application, then relayed this information back to Intellect Service’s servers via innocuous-looking cookies.”

Armed with corporate EDRPOU numbers, the hackers would be in a position to easily identify the exact organization that is now using the backdoored MEDoc.

“Once such an organization is identified, attackers could then use various tactics against the computer network of the organization,” according to Cherepanov.

Scope and Scale of the Attack

Almost 70 % of the NotPetya attacks were Ukrainian businesses, government agencies, and individuals. FedEx admitted recently that some of their systems have been affected significantly and permanently by the ransomware. Somehow three US hospitals were infected, but they had no ties to the MEDoc software.

It is believed (although this has not yet been proved), that the American hospitals may have been inadvertently infected by representatives of the pharmaceutical giant Merck, which uses the MEDoc software.

Ukraine’s Minister of Infrastructure Volodymyr Omelyan told the Associated Press his department alone faces “millions” in related costs. He added that hundreds of his agency’s workstations were disabled and that two of its six servers were compromised.

The Aftermath

Obviously, the attack has been stopped in its tracks and the forensic investigation is ongoing. At this point, there are a few details that are still hazy.

It is unknown, for instance, precisely how Intellect Service removed the backdoor code from MEDoc, or whether they had seen signs that the code had been tampered with.

It is also unknown at this point whether criminal charges will be filed against Intellect Service, but that remains a possibility if it can be proven that the company noticed related attacks but did not take them seriously. As for now, Ukrainian law firms are starting a class-action lawsuit against the company.

We will add more information on this story as it continues to develop.

Find out how partnering with us can help you protect your clients’ most vulnerable aspect of their networks.